Taijiquan’s Thirteen Methods

T he “Thirteen methods” of Taijiquan has several interpretations. Philosophically, the thirteen methods are based on the arrangements of the eight trigrams (bagua) and five elements (wuxing). All Taijiquan systems including Chen style employ “eight intrinsic energies” (ba fa) or types of jin (trained power) and “five steps” (wu bu), which taken together are referred to as the thirteen methods.

Ba fa – eight intrinsic energies

The ba fa embody the eight fundamental methods of training the body’s jin, providing the foundation of all the skills and techniques of Taijiquan. It follows then that the correct practice of Taijiquan must be built upon a clear understanding and identification of these energies. The study of the eight methods is central to understanding and applying Taijiquan’s push hands drills.

The ba fa embody the eight fundamental methods of training the body’s jin, providing the foundation of all the skills and techniques of Taijiquan. It follows then that the correct practice of Taijiquan must be built upon a clear understanding and identification of these energies. The study of the eight methods is central to understanding and applying Taijiquan’s push hands drills.

The eight methods represent eight types of technique: peng (warding off), lu (diverting), ji (squeezing), an (pressing), cai (plucking), lie (splitting), zhou (elbow techniques) and kao (bumping). To be considered as jin rather than simple techniques they must be carried out in the “Taijiquan way”. That is, they must fulfil all the postural and energetic requirements of the system.

To briefly describe each in turn:

Peng

is considered to be the primary jin of Taijiquan that must be understood if the other methods are to be realised. Peng can be a bit confusing for less experienced students; to start with, the term is used in two distinct ways: The first describes a subtle and over-arching quality felt as a physical sensation of expanding from the inside outwards – like a balloon filled with air; the second manifestation of peng is more easily understood, describing a technique usually expressed in the arms in an upwards and outwards direction, preventing an opponent from entering your space.

Lu

is most commonly applied in a downward and backward direction but can be applied in any direction depending on the route of an opponent’s incoming force. Its purpose is to follow the opponent’s movement in order to lead them into empty space (yin jin le kong). In practice this is a subtle type of energy that follows and directs an incoming force drawing an opponent into a compromised position before they realise there is any danger. The person on the receiving end suddenly has a feeling that they are over-extended and out of control. It is likened to the feeling when going downstairs and missing a step in the darkness.

In Chenjiagou lu is sometimes compared to the act of leading a bull with a rope. The bull is much stronger than the person leading it, and if it were a simple test of strength would obviously win. Rather than trying to use force, by guiding it to where you want it to go, the bull can be coaxed into following your intention.

[Example: the transition movement from Lan Zha Yi (Lazily Tying Coat) to Liu Feng Si Bi (Six Sealing and Four Closing) where you lead the movement from the right to the left side]

Ji

is a gradual rolling movement used to unsettle the balance of an opponent. It is carried out in a sequential movement from the feet through the waist and back and out to the arm. Unlike kao, this type of jin is not performed explosively. Not using force but, like water, seeping into a crack and finding any weakness. In Chenjiagou children in the Taijiquan school sometimes play a type of “squeezing game” where they stand in contact with each other and then, all the time maintaining contact, try to unsettle each other’s balance by crowding into each other’s space until one of them has to take a step.

[Example: in Laojia Yilu – in the transition movement from the first Dan Bian (Single Whip) as the practitioner changes direction into Jin Gang Dao Dui (Buddha’s Warrior Pounding Mortar)]

An

In practice, any method where the palm faces an opponent can be classified as an. An is expressed as an energy that is directed downwards in a pressing movement. Applying an, a practitioner directs jin to their hands before pressing down.

[Examples in the form include: Bao Tou Tui Shan (Cover Head and Push Mountain) where you shift weight from the left to the right leg and press with both hands; and the closing movement of Liu Feng Si Bi (Six Sealing and Four Closing)]

Cai

is a combination of rotating, pressing and closing downwards. This type of jin is often used when locking someone’s forearm. It is applying lu with the left side and an with the right, or vice versa. Cai is combined with weighing down using a rolling movement of your forearm to ‘pluck’ an opponent downwards. An everyday example of cai would be the act of plucking an apple from a tree. If you examine the movement you’ll see that rather than holding the apple and pulling straight down, a slight twisting is applied as you separate the apple from its stem.

Lie

can be used by suddenly turning the waist using oblique or diagonal force to either side of your own body and also to either side of your opponent’s body. In practice, this energy is often applied by using, for example, your left leg to control your opponent’s right leg and then using both hands to attack on one side of his body. In Chenjiagou during push hands training practitioners are advised that “when the force comes in sideways you intercept it straight, when it comes straight, intercept sideways.”

Zhou

is a close range method of striking with your elbow. Chen Taijiquan’s elbow attacks can be used in numerous ways to the front, side and rear of one’s body, using either the point of the elbow or the flat of the elbow or upper forearm. If a practitioner understands Chen Taijiquan’s sequential movement method (i.e. how movements unfold through the joints from shoulder, to elbow to the hand) then almost every movement contains within it the possibility of striking with the elbow.

Kao

is utilised when an opponent is very close to attack with the shoulder, back, chest, hip, buttock and other parts of the body. For this method to be successful, the whole body must be in close contact with an opponent before attacking with the appropriate area.

Before any of the methods can be applied correctly, learners have to first develop

some degree of rootedness, weightedness, dantian strength and expansiveness.

They must develop an understanding of what peng means and be able to manifest this in practice.

Without peng it is not possible to manifest Taijiquan’s jin and it follows that you also will not be able to perform any of the other methods properly. This is why it is important to first lay down a strong foundation through standing, reeling silk and especially form training. Together these begin the process of training the correct external posture and internal energetic state. To re-emphasise this point, peng is the basis of all the other types of jin, so we could reasonably describe energies as peng-lu, peng-ji, peng-an etc instead of lu, ji and an etc. Peng jin is realized when a practitioner corrects the common errors of over-reaching (guo), resisiting (ding) or falling short (diu) – finding a balance between these opposing responses to always be in a position of “bu diu bu ding“ – neither collapsed nor over-extended.

Beyond the obvious external characteristics of each method described above,

certain criteria must be fulfilled for them to be considered as

Taijiquan jin and not simply a crude external imitation;

firstly a practitioner needs to develop looseness and pliancy; then from the basis of this looseness, apply techniques with Taijiquan’s sequential joint-by-joint motion; from this basis apply in the characteristic sequential motion; and finally each method should be supported by whole body integrated movement so that the strength of the crotch (dang) and waist (yao) are combined with the rotational movement of the body.

firstly a practitioner needs to develop looseness and pliancy; then from the basis of this looseness, apply techniques with Taijiquan’s sequential joint-by-joint motion; from this basis apply in the characteristic sequential motion; and finally each method should be supported by whole body integrated movement so that the strength of the crotch (dang) and waist (yao) are combined with the rotational movement of the body.

Beyond this, it is important to guard against becoming too fixated on any one for one correspondence between the eight methods and particular movements in the form. It is better to think of them as methods or categories of techniques. It’s understandable that inexperienced learners can feel frustrated sometimes when they want a simple answer to what they think is a simple question eg: Which method is this movement using? What is the application of this movement? There can be many different applications and bringing them out depends upon the requirement of the actual circumstances.

Incorporating the Five Steps (Wu Bu)

People often become overly concerned about Taijiquan’s requirements, to the point that it affects their ability to use the art practically. For example the requirement of rootedness is cited as being essential. But rootedness without agility is of not much use in a real life combat situation. What a practitioner gains in terms of heaviness and stability, he loses through a lack of mobility. Taijiquan’s classic texts teach us that we should “take steps like a cat.” That is, footwork must be precise, stable and agile.

People often become overly concerned about Taijiquan’s requirements, to the point that it affects their ability to use the art practically. For example the requirement of rootedness is cited as being essential. But rootedness without agility is of not much use in a real life combat situation. What a practitioner gains in terms of heaviness and stability, he loses through a lack of mobility. Taijiquan’s classic texts teach us that we should “take steps like a cat.” That is, footwork must be precise, stable and agile.

To achieve this, in practice the eight methods are combined with

the “five steps” (wu bu) – jin tui gu pan ding

(advance, retreat, guard the left, anticipate the right and the position of central equilibrium).

Where the ba fa can be said to represent the hand/body skills of Taijiquan, the wu bu refers to its footwork skills. In reality the two cannot be separated and footwork and body movement must be combined and integrated. These footwork skills provide the foundation for the different hand skills to be applied effectively. Only when the body can move to the optimum position in terms of distance and angle, can the hand skills be applied effectively. The opportunity to apply an attack appears only briefly and has to be taken immediately without hesitation, so there is no time to pay attention to the many factors involved. These have to be ingrained and instinctive. For example, if a person sees an opening to attack with kao they must first step in to occupy the opponent’s space, effectively stepping through him, to apply this close range strike. If the footwork is slower than the upper body they are likely to over-extend and lean too far forwards making the movement ineffectual.

The fundamental importance of developing and synchronising both the body methods and footwork skills is reflected in the saying: „the body follows the steps to move and steps follow the body to change; body movement and footwork skills cannot be forgotten. If any of these is omitted, one does not need to waste his time practising anymore.“

When we combine the eight methods and five steps, therefore, the first and last of each (i.e. peng and ding) are the most important. Beyond techniques they represent over-arching qualities that must be maintained at all times regardless of what action is being carried out.

Extra Methods

Chen Taijiquan has five extra methods which are combined with the aforementioned eight jin: teng (leaping), shan (rapid dodging), zhe (folding), kong (becoming empty; a leading in or neutralising method), huo (to remain lively and flexible). We can think of the first four methods as being types of movement or action through which we can train the eight jin. The last quality – huo – literally meaning “to be alive to change”, referring to the ability to change in an instant and agile way in accordance to unfolding circumstances, provides the same quintessential element as peng and ding.

The trained strength, movement quality and energetic state developed in Taijiquan

are not easy to describe in words

and must be experienced through longtime practice to make possible a deep body understanding.

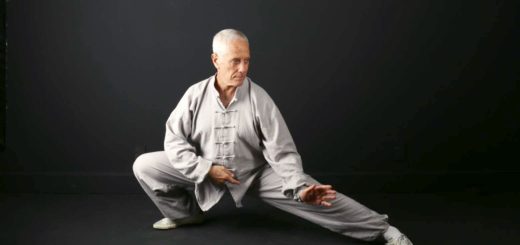

David Gaffney

David Gaffney is co-founder of Chenjiagou Taijiquan GB and co-author of 3 books about Taijiquan (Chen Style Taijiquan: The Source of Taiji Boxing, The Essence of Taijiquan, Chen Taijiquan: Masters and Methods). In 2020 he published another book called Talking Chen Taijiquan.

David Gaffney is co-founder of Chenjiagou Taijiquan GB and co-author of 3 books about Taijiquan (Chen Style Taijiquan: The Source of Taiji Boxing, The Essence of Taijiquan, Chen Taijiquan: Masters and Methods). In 2020 he published another book called Talking Chen Taijiquan.

He has practised Asian martial arts since 1980. His Chen Taijiquan training began seriously in 1996 when he met Chen Xiaowang, later doing a formal discipleship ceremony with him. In 2003 he was formally introduced to his brother Chen Xiaoxing in Chenjiagou in order to receive more personalised training and has carried on training with him to this day.